Increasing sea surface temperatures are imperilling coral reef ecosystems say Australian marine and climate scientists. A new scientific paper reveals that atmospheric warming of 2 degrees celsius is too much for nearly all the world's coral reef ecosystems, including the Great Barrier Reef. The scientists argue that to preserve greater than 10 per cent of coral reefs worldwide would require limiting global warming to below 1.5 °C. This equates to the goal of reducing carbon in the atmosphere to 350ppm, rather than a 2 degree rise or 450ppm that the UN Framwework Convention on Climate Change has adopted as the safe limit at several meetings.

Atmospheric concentration of CO2 currently stands at 392.41ppm. With current pledged reduction in emissions we are heading for 4.4 °C of warming by the end of the century according to the Climate Scoreboard.

Related: The True Cost of Australia's Coal Boom | Greenpeace report: Boom Goes the Reef: Australia's coal export boom and the industrialisation of the Great Barrier Reef (PDF) | The Conversation: - Climate change guardrail too hot for coral reefs?

For Australia, this will have major implications for the Great Barrier Reef and will eventually impact the $5 billion dollar per year tourism and service industries located on Queensland coast with a flow on effect for the Australian economy. But of greater importance is the potential loss of biodiversity this will entail with coral reefs being extremely complex ecosystems with a large number of species.

Coral reefs are found primarily in tropical and warm temperate ocean waters, primarily off the coast of third world, developing or island nations. Australia is one of the few first world countries with substantial coral reef ecosystems. The ecosystems support a large amount of susbsistence fisheries providing needed protein to up to half a billion people in the world.

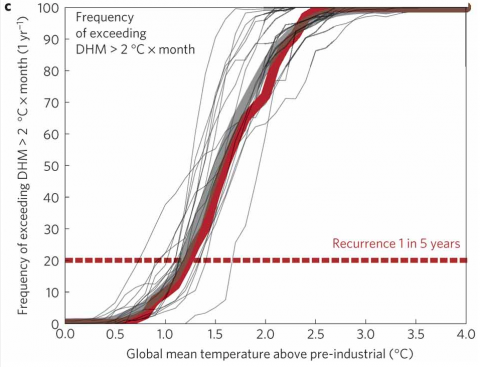

Corals are sensitive to water temperature. With ocean temperatures increasing with global warming mass coral bleaching events are occurring more often and projected to increase in frequency and intensity this century.

Ocean warming is an important stressor to coral reefs causing bleaching events, but nutrient runoff from agricultural production, pollution, ocean acidification and commercial fishing all have a negative impact on reef ecosystems. Mass coral bleaching and mortality events have been observed since the 1980s. Reefs have been able to recover but often it takes 10 to 20 years or more for a reef ecosystem to fully recover from a bleaching event. When bleaching events occur every one or two years corals are unable to recover and a phase shift starts to occur in the ecology of the reef.

When climate changed in the past it was over thousands or tens of thousands of years without additional human caused stressors, allowing coral organisms and ecosystems a chance to shift range or adapt to the changing environment. But we are changing the global environment so rapidly with atmospheric and ocean temperature increases, pollution and runoff from agricultural and land use practices, overfishing the world's oceans, and increasing CO2 which is increasing ocean acidification, that coral reef ecosystems do not have any time to adapt or relocate.

The paper says that "Even under optimistic assumptions regarding corals' thermal adaptation, one-third (9-60%, 68% uncertainty range) of the world's coral reefs are projected to be subject to long-term degradation under the most optimistic new IPCC emissions scenario."

The other major problem corals face is Ocean acidification which reduces the ability of coral and other sea creatures to build their calcerous shells. This reduces the thermal tolerance of these creatures.

The paper - Limiting global warming to 2 °C is unlikely to save most coral reefs (Full paper) argues

Despite the inclusion of optimistic scenarios concerning rates of evolutionary adaptation, our results confirm that coral reef ecosystems face considerable challenges under even an ambitious mitigation scenario that constrains global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures. Our projections suggest that most coral reefs will experience extensive degradation over the next few decades given the present behaviour of corals to thermal stress.

To protect at least 50% of the coral reef cells, global mean temperature change would have to be limited to 1.2 °C (1.1-1.4 °C), especially given the lack of evidence that corals can evolve significantly on decadal timescales and under continually escalating thermal stress. There is little doubt from our analysis that coral reefs will no longer be prominent within coastal ecosystems if global average temperatures exceed 2 °C above the pre-industrial period.

Effective conservation of coral reefs in the face of changing climate and ocean chemistry is likely to depend on our understanding how these other variables affect coral reef resilience. There is little precedent for the rate and magnitude of warming in the recent geological history of corals, including the transition into the warm Eemian period. Further in situ observations and laboratory studies will help refine our understanding about the aggregated likely effects of acidification and warming for individual coral reef ecosystems. Despite these uncertainties, the window of opportunity to save large fractions of coral reefs seems small and rapidly closing."

Threat to coral reefs known for some years

Marine Biologists and climate scientists have been warning of the threats to coral reef ecosystems for some years. From just my recent awareness:

- In 2007 fifty Australian marine and climate scientists issued a consensus statement warning of the impact of climate change on coral reefs and calling for immediate and substantive reduction targets in human produced greenhouse emissions.

- In 2008 marine scientists from around the world issued the Monaco Declaration - a strong statement about ocean acidification accelerating due to increasing carbon emissions caused by human induced climate change. The Declaration calls on Governments to take urgent action to reduce carbon emissions.

- November 2009 - Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg attended the Copenhagen talks in 2009 and warned that Extinction threatens Coral Reefs unless CO2 limited to 350ppm.

- 2009 - Marine and climate scientists appealed for at least a 25% cut in carbon emissions from developed countries like Australia to save the Great Barrier Reef.

- June 2011 - International Programme on the State of the Ocean (IPSO) meeting strongly warned of the damage to the health of the world's oceans and marine life and that if the current business as usual trajectory of damage continues "that the world's ocean is at high risk of entering a phase of extinction of marine species unprecedented in human history."

Cairns Coral Reef Symposium July 2012

In July 2012 an International Coral Reef Symposium held in Cairns warned that coral reefs around the world are in rapid decline. In conjunction with the symposium, over 2000 scientists released a consensus statement on Climate Change and Coral Reefs. (See bottom of this post for full statement)

In a media release Professor Terry Hughes, Convener of the Symposium and Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies stated:

"When it comes to coral reefs, prevention is better than cure. If we look after the Great Barrier Reef better than we do now, it will continue to support a vibrant tourism industry into the future" he said.

"Unfortunately, in Queensland, the rush to get as much fossil fuel out of the ground as quickly as possible, before the transition to alternative sources of energy occurs, has pushed environmental concerns far into the background."

"Australia needs to improve governance of the Great Barrier Reef, particularly coastal development and runoff, to avoid it being inscribed by UNESCO on the List of World Heritage Sites in Danger."

"While there has been much progress in establishing marine reserves around the coastline of Australia, marine parks do not prevent pollution from the land, or lessen the impact of shipping and port developments, or reduce the emissions of greenhouse gasses",

"There is a window of opportunity for the world to act on climate change - but it is closing rapidly,"

Strategies for conservation

While scientists urged action to reduce carbon pollution, they also advocated many positive local actions that could be undertaken to bolster resilience in reef ecosystems including:

- Rebuild fish stocks to restore key ecosystem functions

- Reduce runoff and pollutants from the land

- Reduce destruction of mangrove, seagrass and coral reef habitats

- Protect key ecosystems by establishing marine protected areas

- Rebuild populations of megafauna such as dugongs and turtles

- Promote reef tourism and sustainable fishing rather than destructive industries

- Use aquaculture, without increasing pollution and runoff, to reduce pressure on wild stocks.

Natalie Ban, an ARC Postdoctoral Fellow in Program 6 (Conservation Planning for a Sustainable Future) at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University did a recent (March 2012) about the Strategies for conservation under climate change. Watch the video:

Differences between Caribbean and Indo-Pacific coral systems

But not all coral reefs have been impacted the same by climate change and other human caused factors. Reef systems in the Caribbean have suffered more degradation to date than coral reef ecosystems in the Indo-Pacific region. Dr George Roff and Professor Peter Mumby from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and The University of Queensland presented a paper in July at the Cairns symposium which argued that coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific Ocean are naturally tougher than the Caribbean reefs.

"The main reason that Indo-Pacific reefs are more resilient is they have less seaweed than the Caribbean Sea," Dr Roff said. "Seaweed and corals are age-old competitors in the battle for space. When seaweed growth rates are lower, such as the Indo-Pacific region, the reefs recover faster from setbacks. This provides coral with a competitive advantage over seaweed, and our study suggests that these reefs would have to be heavily degraded for seaweeds to take over.

"This doesn't mean that we can be complacent - reefs around the world are still heavily threatened by climate change and human activities," he says. "What it indicates is Indo-Pacific reefs will respond better to protection, and steps we take to keep them healthy have a better chance of succeeding."

"Many of the doom and gloom stories have emanated from the Caribbean, which has deteriorated rapidly in the last 30 years," says Professor Mumby. "We now appreciate that the Indo-Pacific and Caribbean are far more different than we thought."

Tipping points, Regime shifts and living on borrowed time

As atmospheric and ocean temperatures increase, the frequency and intensity of bleaching events will degrade reef ecosystems with a steady regime shift over many years from coral dominance to macro-algal dominance composed of organisms such as algae, seaweeds and jellyfish. Professor Terry Hughes, Director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies did a recent (March 2012) video talking on Tipping points, regime shifts and borrowed time in a 38 minute talk:

The cost of saving reef ecosystems

So do we just say goodbye to our coral reef ecosystems? Have a think about the impact. Coral reefs provide habitat for over a million species. That is a lot of biodiversity to lose. Approximately half a billion people are dependent wholly or to some extent on the productivity of coral reefs. Are we ready to transfer their dependence on ocean productivity to land productivity?

Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg did a presentation at the symposium in July on the cost of saving reef ecosystems. IPCC analysis concluded that slowing global GDP growth by 0.12 per cent a year over the next 50 years would be enough to stabilise global temperature.

"That expenditure is the equivalent to taking off one year of GDP growth over the next 50 years," Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said.

"It would enable atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide to stabilise at levels that will give coral reefs a chance.

"Without this action, they don't stand a chance.

"It's very clear that we have one last opportunity to make the changes that are needed to preserve this brilliant and economically important ecosystem on our planet.

"And the costs are minimal when they are aligned against the huge and impossible costs of trying to adapt ecosystems like coral reefs to the changes being inflicted on them."

Rising sea surface temperatures, caused by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases, including CO2, in the atmosphere, increase the likelihood of mass bleaching events which kill coral reefs.

Reef restoration methods - while effective at some local scales - are not economically-viable on a large scale, according to Professor Hoegh-Guldberg.

"To replant the Great Barrier Reef by planting fragments that cost $5 a piece to grow in the aquaculture facilities across 40,000 km² of the Great Barrier Reef would cost $200 billion," Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said.

"If we then decided that we would want at least 20 different species within those communities, the cost would be $4,000 billion. The numbers are quickly astronomical and impossible."

Professor Hoegh-Guldberg said as the situation now stood, modelling for the upcoming fifth assessment report of the IPCC showed that under most scenarios coral reefs were in extreme peril from warming oceans.

He said as temperatures increased, so would the frequency of 'killer' coral events.

"Considering that coral communities take at least 10 to 20 years to recover - having a mass bleaching event every two to three years is essentially to admit that those coral communities no longer survive and recover," he said.

Australia takes a small step declaring marine reserves network

The Australian Government took a small step forward in June 2012 when Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke announced the world's largest network of marine reserves, including in the coral sea. While commercial fishing operators were disgruntled at the announcement, the Australian Conservation Foundation said it would have little impact on recreational fishing and help with recovery of fish stocks and eliminate destructive bottom trawling.

Laurence McCook PhD, Pew Fellow in Marine Conservation, did a recent presentation on Benefits of Marine Reserves:

ACF's healthy oceans campaigner Chris Smyth said in a media release: "Recreational fishers will also benefit because of the removal of bottom trawling from almost the entire Coral Sea Marine Reserve and commercial tuna longlining from a large area along the eastern boundary of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Recent scientific research around the Barrier Reef found causal links between marine reserves and the subsequent recovery of ocean life and its spill over into fished areas."

"Most people living on the coast will see through the wildly exaggerated and unfounded claims made by scaremongers about the economic impact of marine reserves" he said, "While some commercial fishers will need to make changes to where or how they fish or may choose to leave the industry, the government will provide up to $100 million in funding to help them adjust to the national network."

"Australian and international scientists agree there is a need to reduce cumulative pressure on oceans from fishing, the oil and gas sector and climate change." he concluded.

The announcement was endorsed by the IUCN World Conservation Congress meeting in South Korea who called it one of the most significant advances for marine environmental protection in Australia's history and urged global community to support similar initiatives. The initiative was started by the Howard Government in 1998.

Oil and gas mining have been banned from the Coral Sea reserve and the reserve located off the Margaret River area of South West Australia.

You can watch a 21 minute video presentation published in March 2012 on Climate Change and the projection of coral reef futures by Professor Sean Connolly, Chief Investigator and Program Leader with the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and a Professorial Fellow within the School of Marine and Tropical Biology at James Cook University.

Coal power and coal export is causing climate change

Early this year I reported on the expansion of coal, coal seam gas and port facilities and it's impact on the Great Barrier Reef. Greenpeace had issued a report Boom Goes the Reef: Australia's coal export boom and the industrialisation of the Great Barrier Reef (PDF), in which they highlight the massive expansion of liquified gas and coal port facilities underway and planned and the massive increase in ship traffic through the World Heritage Area this will generate.

Coal exported from Queensland ports in 2011 amounted to 156 million tonnes. The expansions planned will result in the export of 944 million tonnes per year by 2020. While 2011 saw 1,722 coal ship movements, by 2020 this could expand to 10,150 all passing through the Great Barrier Reef marine park. Driving these coal port expansions are new coal mines planned or being expanded in the Bowen Basin, Galilee Basin and Laura Basin.

Increase in bulk carriers through the Great Barrier Reef is likely to cause increasing impact and damage on the reef. There are now on average two major shipping incidents being reported every year. Groundings and subsequent pollution from incidents like the grounding of the Chinese bulk coal carrier the Shen Neng 1 in 2010 will have a cumulative impact.

Australia's continued reliance on coal power for electricity and expansion of it's coal export industry is contributing to and inexorably driving the world past tipping points such as the disintegration of Arctic summer sea ice, melting of the Greenland ice sheet, and the start of destabilisation of the West Antarctic Ice sheet. We are living on borrowed time and unless we can reverse some of the damage we are doing we are making a more hellish and inhospitable world to be lived in by our children and future generations.

Consensus Statement on Climate Change and Coral Reefs

The international Coral Reef Science Community calls on all governments to ensure the future of coral reefs, through global action to reduce the emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, and via improved local protection of coral reefs. Coral reefs are important ecosystems of ecological, economic and cultural value yet they are in decline worldwide due to human activities. Land-based sources of pollution, sedimentation, overfishing and climate change are the major threats, and all of them are expected to increase in severity.

Changes already observed over the last century:

- Approximately 25-30% of the world's coral reefs are already severely degraded by local impacts from land and by over-harvesting.

- The surface of the world's oceans has warmed by 0.7°C, resulting in unprecedented coral bleaching and mortality events.

- The acidity of the ocean's surface has increased due to increased atmospheric CO2.

- Sea-level has risen on average by 18cm.

By the end of this century:

- CO2 emissions at the current rate will warm sea surface temperatures by at least 2-3°C, raise sea-level by as much as 1.7 meters, reduce ocean pH from 8.1 to less than 7.9, and increase storm frequency and/or intensity. This combined change in temperature and ocean chemistry has not occurred since the last reef crisis 55 million years ago.

Other stresses faced by corals and reefs:

- Coral reef death also occurs because of a set of local problems including excess sedimentation, pollution, habitat destruction, and overfishing.

- These problems reduce coral growth and vitality, making it more difficult for corals to survive climate changes.

Future impacts on coral reefs:

- Most corals will face water temperatures above their current tolerance.

- Most reefs will experience higher acidification, impairing calcification of corals and reef growth.

- Rising sea levels will be accompanied by disruption of human communities, increased sedimentation impacts and increased levels of wave damage.

- Together, this combination of climate-related stressors represents an unprecedented challenge for the future of coral reefs and to the services they provide to people.

Across the globe, these problems cause a loss of reef resources of enormous economic and cultural value. A concerted effort to preserve reefs for the future demands action at global levels, but also will benefit hugely from continued local protection.

Original statement signed by over 2000 marine and climate scientists.

Sources:

- Limiting global warming to 2 °C is unlikely to save most coral reefs (Full paper)

- Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, The Conversation, 17 September 2012, - Climate change guardrail too hot for coral reefs?

- Media Release 9 July 2012 - Save what remains of our reefs, scientists urge

- University of Queensland Media Release 8 July 2012 - Price to save coral reefs is one year of GDP growth

- Coral Reef Symposium media release - 12 July 2012 - Our coral reefs: In trouble - but tougher than we thought

- International Coral Reef Society, July 2012 - Consensus Statement on Climate Change and Coral Reefs

- Australian Conservation Foundation Media release, 10 September 2012 - Marine reserves are good for recreational fishing

Takver is a citizen journalist from Melbourne Australia who has been writing on climate change, science and climate protests since 2004. This article was originally published at San Fransisco Bay Area Indymedia and on his blog.