Courtesy of The National Indigenous Times - Wednesday May 30 edition - Editor Stephen Hagan's interview with Aunty Bonita Mabo, wife of Eddie 'Koiki' Mabo

http://nit.com.au/chat/1147-aunty-bonita-mabo-wife-of-eddie-koiki-mabo-c...

Who's your mob Aunty Bonita?

I was born in Ingham in north Queensland. My people (Neehows) are from the Malanbarra Clan from Palm Island on my mother's side.

My Dad can trace his people to Tanner Island in Vanuatu.

My Grandmother had seven daughters and they all lived together with their family in the gully in Halifax.

SH: What can you tell me of your school years?

All us kids went to Halifax State School. I really liked maths and history and got on well with all the teachers. Back in those days we never had racism at school or at least I never experienced any.

What I can remember is walking 3 kilometres from our home to school along the road and sometimes we'd take a short cut and cross over the railway line. Us kids enjoyed the long walk, talking and enjoying the bush around us.

SH: Did you go to high school?

No I never went to High School. Only people who had money went to High School in my time. I went – like most of the other Aboriginal kids around 13 and 14 – went off to work for white people washing and polishing their floors.

SH: When did you meet Eddie?

I was quite young back in 1958 when I first met Eddie. He came to Halifax for a wedding when my cousin married his cousin.

After the wedding he went back to cutting cane up near Innisfail.

It wasn't long after when we met at another wedding. When my cousin and me were going to the Hall Eddie and his mates were hanging out the pub window calling out to us. We kept walking ... I saw him later at the wedding.

He made a big impression on me.

I eventually married Eddie a year after I met him, in 1959, and together we raised ten children: Eddie Jnr, Maria Jessie, Bethal, Gail, Mal, Malita, Celuia, Mario, Wannee and Ezra.

SH: What are your earliest memories of life with Eddie?

He worked long and hard and was prepared to follow the work wherever it was. I seemed to be having children at different places he worked.

But what was clear with Eddie was that it was important for his kids to know his culture and learn the dance.

He seemed to have a passion about culture and often spoke about the need – even though he was far away from his Island – to teach the culture and not lose it.

SH: When did Eddie get involved in Indigenous organisations?

Eddie was always on about doing the right thing and making a difference. When we finally settled in Townsville he learnt a lot from his work mates on the waterfront. He used a lot of those actions from those friends to drive him on to achieving things like setting up the legal service, the housing company and of course the Black Community School.

It got to the stage when I used to say to my self 'he we go again – he's home and all he wants to do is talk politics'. It was like Eddie couldn't get enough of politics.

It was like there weren't enough hours in the day to do all the things he wanted to do.

He also loved reading books about his people and was curious about what other people, anthropologists and those people, were saying. He was hungry for knowledge and read and spoke to as many people as he could.

SH: When did Eddie start on his crusade to fight for title to his land on Murray Island?

In the 1970s when Eddie was working as a gardener at James Cook University and doing his studies he had a conversation with Dr Noel Loos and Professor Henry Reynolds who told him that he didn't have rights to his land on Murray Island in the eyes of the white man and according to their laws.

Eddie was so wild with what they said that he started to read more about why they would say that.

I think it was around 1981 at a Native Title Conference at James Cook University when he made a speech about his land back on Murray Island that he met a lawyer who wanted to do a test case to see how it would go in court.

SH: Did many of his Torres Strait Island relatives and friends in Townsville at the time supported Eddie in his case?

No, not really. They didn't really understand what he was on about and many of them didn't really want to get into the politics of the case.

He did have one strong supporter in Donald Whaleboat who was behind him all the way.

It made me sad to see that his people didn't support Eddie or show an interest in his case. I'm sure he would've loved to have sat down and gone into the details with them and perhaps their contribution would have encouraged him.

SH: Did it affect him that he wasn't getting the level of support he thought he should have?

It was pretty difficult on him at first as he felt the only people he could talk with were Dr Loos and Professor Reynolds and of course, whether we liked it or not, he talked about it all the time at home with me and the kids.

The thing that really affected Eddie and also me ... was when he went back home for meetings with his community on Murray Island. I clearly remember the Mayor saying for him not to bring that southern nonsense up to the Island with him.

I also remember him ordering Eddie out of the community meetings. And of course I followed him out of the community meeting with other supporters.

It was strange when Eddie passed on and we went back to the Island, the same Mayor came up to me and asked me to share his ideas with him. He said he wanted to use his ideas on his community to improve it.

I told him straight away that I wouldn't share it with him and I will take those views Eddie shared with me to my grave.

SH: Where were you back in 1992 when the Mabo decision was being handed down in the High Court in Canberra?

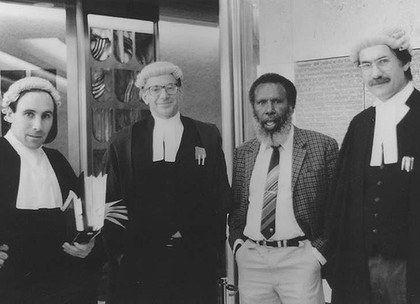

I got a call from those wonderful lawyers - me and my family owe them the world for their hard work for so long and who stuck with Eddie all those years with his case - and they told me that I should make my way to Canberra as the decision was going to be handed down in a couple of days.

You know I went to every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island organisation in Townsville and asked them for some petrol money to get to Canberra and not one of them helped out.

They reckon they didn't have money for that kind of thing. Now a lot of them are benefitting from Eddie's case and of Native Title generally.

It really made me so upset that after knocking on all their doors and talking to the head people that not one single organisation could give me a dollar. Not even five dollars.

I knew they had money but none of them really supported Eddie or his court case except for a couple of close family members and friends of ours and the other claimants (David Passi and James Rice representing the Meriam People).

SH: So how did you get to Canberra?

I rang my son Mal in Cairns and asked him how his car was going. He said it was in the garage getting some repairs done. I told him about the phone call from his father's case in Canberra and he got the car out of the garage and came straight to Townsville.

We drove to Sarina and picked up another couple of my daughters and we drove and drove and were on the outskirts of Sydney when we got word that Eddie had won at the High Court on June 3.

SH: What did you do to celebrate?

We decided we wouldn't drive on to Canberra and instead pulled over at a shopping centre and bought some sandwiches and cups of tea.

We all shared some private moments reflecting on Eddie's case and congratulated him on his success in our own way and then got in the car and drove back to Gail's place in northern New South Wales where we had a shower and a bit of a rest.

Mal and the other kids made a big banner of the win and put it on the side of the car where it stayed all the way back to Townsville.

SH: Did you get any other assistance with the travel expenses?

The most disappointing part about the Mabo case is that we never got a cent off anyone – it wasn't through lack of trying ... and it wasn't that I was asking for airfares – it was only for petrol money to get to Canberra and back for me and the kids.

Eddie and the good spirits must have been looking over us on that long trip as we only had enough petrol and food money between us to return home. If we'd had a flat tyre we wouldn't have been able to have it fixed up ... that's how broke we were.

And to think that High Court decision has made such a big difference to many of our people's lives. Many of them have made a comfortable living from the Mabo case.

Here I am today, sick with poor eye sight and haven't got 2 bob to rub together.

SH: On reflection today what are the positives and negatives to come out of the Mabo judgement?

The positives would have to be that it got our people now identifying with the tribe they are connected with. Before Mabo I don't recall anyone talking about the tribe they came from or on whose land they were on.

Everyone's doing acknowledgements and welcome to country and even the politicians are doing the same. None of that happened before the Mabo case.

Now everyone's out there doing the research and gaining pride about their people's country.

The negatives would be that Native Title – that came from Mabo – has split families up. It seems to me that the spirit of Mabo – what Eddie was aiming for; of being able to claim title to his land – has gone to the bad side where people think there is a lot of money to be made from native title and will exclude certain families so they can have most of that money they believe is out there.

It was never about money for Eddie ... it was about gaining title to what is rightfully his as handed down through the generations.

It really saddens me to see so much fighting go on over boundaries ... a couple of metres here and a couple of metres there. Many of the people would have no idea where their boundary was if it wasn't for white anthropologists telling them. How sad is that?

SH: What do you wish for in the future?

My eyesight is failing me now and I've got other health conditions ... but having said that I'm happy with the 20th anniversary celebration of the High Court decision and I will take part in them as much as possible with my health.

But after the celebrations I'd like to take it easy and just be with my children and grandchildren.

On the 10th of June the ABC is showing the film 'Mabo' [directed by Rachel Perkins and starring Jimi Bani as Eddie and Deborah Mailman as Bonita] and I'm excited about being a part of the making of the movie.

I guess there will be more interviews after the movie comes out – which I really don't like doing these days.

And then last week I was flown down to Sydney to the Museum where they gave me a preview of a Madame Tussaud's wax statue of Eddie and it scared me.

After all these years of living without this strong proud man I was suddenly face to face with a wax statue that looked scarily like Eddie.

I loved him so much and seeing him eye to eye on that day brought tears to my eyes.

And in the same edition of The National Indigenous Times (May 30, 2012):

http://nit.com.au/opinion/1143-when-i-first-met-eddie-koiki-mabo.html

WHEN I FIRST MET EDDIE 'KOIKI' MABO

By National Indigenous Times Editor Stephen Hagan

From living in a humpy on the fringe of a prosperous sheep grazing country town in far south west Queensland to a private school education in Brisbane, life was fascinating – if not challenging – up until then, but all those appreciable changes in my social and educational landscape made my thirst for knowledge of a political nature even more insatiable.

I lived in a life of total opposites: of disparate housing, employment, health and social opportunities to my white counterparts; of standing at the front of the queue waiting patiently to be served only to witness a non-Indigenous person waved to the front of the line by the proprietor for immediate service and of being roped off in the cinema and being refused access to adjacent seating arrangements with my white school friends.

It took me a while to discern the repugnant dynamics at play of being allowed to sit with my white friends at school from Monday to Friday but then accept without dispute the enforced separation from them at the local cinema on a Saturday night. I was very young. But how was I to know that tolerating segregation, as a norm, was improper?

On reflection today, the truth is often more vexatious, as the desire to enjoy Western or War movies back then by leaders of our community, whilst being segregated, was far greater than organizing mass protests through boycotting the cinema and hurting the proprietor in the hip pocket.

During my senior year at boarding school I was enthralled by literature of the power of protest and often found myself drawn, outside school hours, to Black Power meetings in Brisbane listening to the powerful oratory of black pride by Dennis Walker, Sam Watson, Cheryl Buchanan and Pastor Don Brady, to name a few. These controversial leaders whetted my appetite for knowledge and enhanced my appreciation of the need to protest for social justice.

Immediately after boarding school, and once again with a sea change through a life changing journey to Townsville in north Queensland to undertake tertiary studies, I came across a remarkable Australian who not only left an indelible impression on me but also the nation. The extraordinary person I speak of is Eddie "Koiki" Mabo.

On my first night in the Halls of Residence at the Townsville College of Advanced Education, my deep sleep was broken by the eerie noise of the (Bush Stone) Curlew Bird. It sounded like a high-pitched cry of a woman in distress. As a child growing up in Cunnamulla the sound of a Curlew, rare out west, was seen by murries as a message of death. It frightened my people who thought it meant that someone close to them, but far away, had passed on. Unfortunately it was a sound I had to get used to as those pesky birds were on song most days of the year.

The most pleasing thing about venturing north to engage in tertiary studies was the very visible presence of black people. Back then (1979) it was generally accepted that of a population of 100,000 people living in Townsville over 10% were Indigenous.

After a couple of years in Brisbane I often found myself travelling from one side of town to the other for school sporting events without seeing a single black face. I appreciate the population ratio makes provision of visibility of colour more palpable but nevertheless it was a wonderful sight to behold for someone as impressionable as I was at that time in my life to see so many black faces.

In this new environment I was able to study and socialise with other Indigenous students, a combination of school leavers as well as mature age students. I most admired Ray Warner, who had started his working life as a fettler (labourer/water boy) on the railway and decided he could achieve more in life by going back to study.

Ray graduated as a teacher and later pursued a medical degree at Newcastle University. My Dad always said that everyone has ability, regardless of race, and it is just a matter of how far an individual is prepared to go to take advantage of opportunities presented to them—and Ray grabbed opportunities with both hands. Ray has now logged in successful decades of medical practice.

After a month of settling into the daily grind of studies in Townsville I became good friends with many students of Torres Strait Islander descent. Townsville had a large Torres Strait Island population, many of which were the sons and daughters of workers brought to the mainland to build the vast network of railway lines that travels the length and breadth of the state. Like the South Sea Islanders who were black-birded to Australia from the Solomon Islands in the Pacific to do the menial work in the canefields of Queensland, the Torres Strait Islander people were viewed also as hard workers who could be relied upon to work under difficult conditions in the State's hot interior.

It soon became apparent to me that many local Aboriginal people in Townsville viewed the Torres Strait Islander people as having a superior attitude towards them. Although I was aware of the talk amongst Aboriginal students from Townsville I never had any direct evidence of differing attitudes between Aboriginals and Islanders. Certainly at the University there was no hint of any such divergence between the two races and I proudly became close friends with Dalton Cowley, Judy Christian and Elo Tapin, to name a few.

I was conscious though that white people in Townsville talked about the Islanders as being more assimilated than Aborigines. Over the years missionaries and white employers may have reinforced that belief to the Torres Strait Islander folk. And I heard several lecturers say how they were more advanced at first contact in their stage of cognitive evolution than Aborigines; evidenced by their habit of living in houses in settled communities, of cultivating the soil and by their skills in agriculture, in the construction and navigation of canoes, and the use of the bow and arrow. I just put that talk down to the white man trying to divide and conquer. I certainly didn't believe the rhetoric. To me the Torres Strait Islanders were my equals—both in the lecture theatre and after hours at social functions.

However the one Torres Strait Islander friend I grew very fond of and looked up to was Eddie Mabo. Known affectionately by his people as Koiki, Eddie was highly regarded for his work in establishing the first independently run Black Community School in Townsville; the first institution of its type in Australia.

At times I didn't know where he found all of his energy as he was trying to balance his studies with a dozen or so Indigenous organizations that required a lot of his time on a voluntary basis. But the workload never fazed Eddie. He was always on the move and constantly challenging himself and those around him.

Eddie and I would often chat, in the corridors before class or outside the College cafeteria on the grass, about political events as they related to Indigenous issues. He was quick witted and widely read, and I found him to be fiercely proud of his Torres Strait Islander background, especially his homeland of Murray Island (Mer).

Whilst many of my Indigenous classmates were out to maximize their social opportunities away from their communities they tended to have less time to engage in robust political debate. Certainly debate was omnipresent on issues of culture, but not so much – from my perspective – on politics.

Eddie loved politics and as an avid student of politics I preferred long yarning sessions with him than hanging with the more popular personalities whose wit and musical prowess made them the centre of attention.

I found Eddie to be a visionary – if not idealistic – but nevertheless someone who cared passionately enough about his people to want to plan decades ahead of what might be.

Eddie was instrumental in setting up most of the Indigenous organizations in Townsville and with his skills gained from his colleagues in the waterside workers union he dared to pursue justice in all facets of life.

I was fortunate - and some might say patient enough out of all the other students who had equal access to Eddie as I did – to have shared those intimate moments in deep political dialogue with Eddie. As such I gained an insight into a complex and passionate man that had his dream realized – albeit after his passing – on an issue as paramount as native title.

Perhaps in another time and place I might also have taken the time out to chat with an Indigenous philosopher about astronomy – if there was one around then - such was my appetite for knowledge. In this instance I feel blessed today to have spent time listening to this wonderful man share his inner most thoughts of his aspirations for his people.

The men who were credited with guiding Eddie into making a stance on native title, Dr Noel Loos and Professor Henry Reynolds were not isolated intellectuals who happened to chat with him in passing ... but rather, they were strong advocates of Indigenous people generally.

Dr Loos taught Eddie and myself in History and although we weren't taught directly by Professor Reynolds we were taught, however, by his wife Margaret in Education studies. Margaret became a Labor Senator years later. Professor Reynolds used Eddie as a guest lecturer in cultural studies at James Cook University, even though he was a student at the time.

It therefore did not surprise me when I learnt in 1992 that Eddie Mabo, along with David Passi and James Rice, asserted, to the High Court of Australia that since time immemorial the Meriam people had continuously occupied and enjoyed the Islands and had established settled communities with a social and political organization of their own.

I followed the case for many years and was saddened when Eddie died, at age 55, of cancer just four months before the High Court of Australia brought down its historic ruling on 3 June 1992. Known as the Mabo decision, it launched Native Title in Australia and put an end to successive governments' claims that Australia was Terra Nullius, a Latin term that meant "no one's land'.

I'm delighted to have on the cover of this edition an exclusive interview of the person who knows Eddie the best; his beautiful wife, Bonita.

Stephen Hagan is a Kullilli traditional owner of south-west Queensland, 2006 NAIDOC Person of the Year, and a multi-award winning author and film maker.

Comments

Amazing what some make of beginnings

These insights are exactly well considered insights, it's amazing what something is about in the beginning and what other people who go on to give themselves titles and corporations then make it about

Awesome ...

Awesome ... THANKS for great efforts and BEST WISHES for great reward !!

Aunty Bonita Mabo very rich in many ways

Aunty Bonita Mabo sounds rich to me, maybe not in the monetary sense, but very rich in many other ways.